Ep 2: Harnessing Randomness (with Denis Noble)

What is the role of random, stochastic events in biology? How does our body react to such events? Does the presence of random events in our brains give us the illusion of freewill?

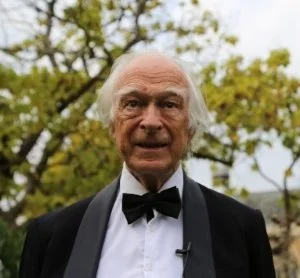

Tune into this episode to hear Marty and Art talk to Denis Noble, an Emertis Professor at Oxford. Noble has written over 500 scientific articles and 11 books but may be most well known for developing the first mathematical model of heart cells in 1960. Recently, Noble published the book: “Dance to the Tune of Life,” where he notably discusses the necessity and importance of random events that occur within and between our genes, cells, tissues, and organs. '

-

MM: I’m Marty Martin.

AW: And I’m Art Woods.

MM: Welcome to the Big Biology podcast. Today, we're talking with Denis Noble, Emeritus Professor of Biology at Oxford University. Denis describes a radical new view of causality in biology. In our conversation, we get into the details of several of his ideas about biological complexity, including: what DNA actually does; what, besides DNA, we inherit from one generation to the next; and how randomness can be harnessed to carry out useful functions.

AW: Before we get into it, just a few comments on the structure of our podcast. For each conversation with a guest, we're going to release two versions of the recording. One of the versions will be long—a lightly edited version of the entire, raw conversation—and that's what you'll get in the rest of this podcast. We'll also release a much more compressed version that hits just the highlights, and lasts for just 5-10 minutes. If you want a short version of our conversation with Denis, you can find it on our website.

.....

(intro music)

.....

MM: We're here with Denis Noble, and Denis has a book that's come out recently, called Dance to the Tune of Life. We'll be spending a lot of time talking about the material in that book. Denis, correct me if I'm wrong, but that sort of extension and development of ideas that were in a book that came out a few years prior, called The Music of Life, and I'm sure we'll talk about that one too. Wow, we have so many different items to get to, I think we'll just maybe jump right in and first set the table by asking you as a—to my knowledge—relatively classically trained physiologist, what led you to turn the corner and start thinking more about evolutionary biology?

DN: Can you imagine that I was the examiner of Richard Dawkins in 1966?

MM: Wow!

DN: And that was because he was working with the very distinguished ethologist, Niko Tinbergen—incidentally, the only ethologist ever to get a Nobel Prize for physiology and medicine. And the reason he did that is that Niko Tinbergen made a very important point, which was that behaviour is just as much an evolutionary characteristic as structure and function. And that led, of course, to many developments in behavioural biology. And Richard Dawkins was working under him to do his doctorate using time sequences. That's working out how long an animal does this, that, the other, and so on. And you can analyse those with a particular bit of mathematics. This gets slightly technical. It happens to be called Laplace Transforms. But don't worry about that. The important part of this story is that I was thought—in those days, because I was deep into mathematical modelling—to be almost the only biologist in the university who could cope with a bit of advanced mathematics.

(MM laughs)

03:09

DN: So, they got an ethologist from outside the university to be, as it were, the scientist from the field, and I was asked to cope with the mathematics! And I'll tell you a little secret: I actually didn't know very much about Laplace Transforms, so I went out and bought a book on it. And I've never regretted that! Now, ten years later, The Selfish Gene comes out. 1976—ten years later—I organised the first debate on The Selfish Gene in Oxford. So there's my credentials; goes back 40 odd years.

MM: Okay, excellent. Wow, so was it something particular about the material in The Selfish Gene that motivated you to write the book and many papers? That's quite a lot of output, given the experiences.

DN: I can give you chapter and verse on what the problem was. The debate was actually involving two scientists: Richard Dawkins and me as the scientists, and two philosophers: a very famous Canadian philosopher called Charles Taylor—who was in Oxford at that time—and a very famous British philosopher, Tony Kenny, Anthony Kenny. And Richard gave a brilliant ten-minute summary of The Selfish Gene. I have to give Richard this. His writing is absolutely fantastic.

MM: Absolutely.

DN: He is so convincing!

(MM laughs)

04:37

DN: Now, what happened then was that Tony Kenny simply said, "I don't need ten minutes. I've only got one question for you Richard. And that is, if all I knew of the English language was the letters of the alphabet, I would not thereby be allowed to say that I could understand Shakespeare." Now that's a trite remark, but that wasn't the point of course. It was really to find out what Richard Dawkins would say. So Richard said—and I remember this absolutely clearly—he said it many times since: "You know, I'm not a philosopher. I'm a scientist. I'm only interested in truth." Now, I don't know what the listeners will think of that [interference]. Well actually, there was somebody in the audience who's a French person who butted in and said, (DN imitates French accent) "What is truth!".

(MM and AW laugh)

DN: I thought, well yes, that's the problem! And it was from there on I started to go through The Selfish Gene as a book, and started dissecting it. And what I found was that as you dissect it, and you work out what it actually means, you find that it can be deconstructed. I do that in my new book. There's a whole section in one of the chapters that deconstructs what I see to be the misleading characteristics of Neo-Darwinist thought. And I think most of those come from misuse of metaphor. And The Selfish Gene is that! How can a bit of DNA sequence be selfish? You know, you and I can be selfish. I'm certainly selfish sometimes, and how can a simple molecule—well it's not a very simple molecule, I know. But anyway, can any molecule be selfish? I don't—I'm partly joking here, but there is a serious point behind it: I think it's the misuse of a metaphor.

MM: Right, okay. And that's a perfect segue into sort of—let's talk about the book. And Art, I think you wanted to extend this idea about, what does DNA do?

AW: Yeah I think, you know one of your big points in the book is that there's many other things besides DNA and DNA sequences that are inherited. And I think, you know, for our listening public, that's maybe an important point to deconstruct a bit, because I think just like many molecular biologists have come to believe that DNA is the computer program or the blueprint of life. I think the public accepts that as well; they've absorbed that from the sciences over the last 50 years, and yet you have this alternative point of view. So maybe lay out that alternative point of view.

07:14

DN: Yes, very quickly: we all inherit, of course, a complete cell formed by the fusion of the cell from the father, the sperm, and the egg from the mother. So it's fairly obvious in one sense that we must be inheriting more than DNA, because that cell is vastly more than DNA. You know, if I represented the cell by imagining that a molecule is about the size of my fist—that's a huge expansion in size of course, but it gives an idea—you know, the edge of the cell would be way up in Scotland. I'm down in the South of England. I'll tell you something very important: at a molecular level, the dimensions of the cell are huge! Moreover, it's packed with stuff. It's packed with little bits of pieces here, there, and everywhere. We call them big names of course: mitochondria, ribosomes, and so on. And what are most of those composed of? Of course, proteins, which are indeed using the DNA as templates to form them, but the great majority of it otherwise is membranes. What are membranes made of? Lipids, cholesterol, and goodness knows how many other molecules, none of which is coded for by DNA. So it's obvious, if you do the calculations—I've done that—you can show there's as much information there as there is in part of the genome that is used to make proteins.

AW: So is that information that's extra-genetic, that's not in the DNA. Is it faithfully transmitted from one cell to the next? One generation to the next?

DN: Well, it has to be! We inherit the whole cell!

(MM and AW laugh)

DN: If that [interference]. It's obvious isn't it? But I think what you're getting at a slightly different question, which is this: if you change that, does that get inherited? In the way which, if you change a bit of DNA, mutate it, that does get inherited. Now there are various ways in which you can demonstrate that. A beautiful experiment done by some scientists in the Fish Institute in China, in Wuhan. What they did was to take two completely different species of fish. One was a goldfish, a nice crunched up, almost globular fish. The other was a carp, which is a great long extended fish, right? And what they then did was to take a fertilised egg cell out of the goldfish—remember that's the stubby one. They took the nucleus out. Then they went to the carp and took the nucleus out of the carp. And they inserted that nucleus into the fertilised egg cell of the goldfish. What fish would you get as a consequence of that? Most people would say it must be a carp. What you get is intermediate. And indeed the title of their paper is Cytoplasmic—that means cellular—Effects on, and then they explain what kinds of effects there are. And what you find is that the intermediate organism that is produced from that cross is, it's sort of intermediate in anatomy. You can see it just by looking at the fish. It's somewhere between a goldfish and a carp. So we can actually experimentally demonstrate that if you take the cellular inheritance from one species, and you combine it with the nuclear inheritance of another, you will get something in between.

11:01

AW: So if we demote genes and genomes slightly from being, you know, a book of life or a blueprint for life, and recognise these other forms of inheritance, then what would you say is the role of genes and genome? You know, in your book you talk some about Barbara McClintock's take on the genome as being an organ of the cell, and I really love this idea. And it makes it seem like, you know, it switches around the causality so that the genome itself is subservient to this larger entity that's controlling and cooperating with it. Is that a fair characterisation?

DN: Absolutely, exactly accurate. That's exactly what I say. Now, let's do the following thought experiment. It can't be done at the moment, but I think people can see what I'm going to say is correct: If I could take one of our cells and pull the DNA out as a complete long string—well actually it would be of course a number of strings and the different chromosomes—but let's imagine we pull it out and we place that very thin thread because it's incredibly thin. It's only after all one molecule thick. And we're gonna put that into a scientific pot called a petri dish. It's where you put fluid that will resemble the fluid that occurs in the blood for example, with the right salts, the right nutrients and so on. So there you've got the DNA in the pot, with nutrients as many as you wish, I don't mind how much [interference] stuff you put in there. I tell you I could keep that DNA for ten thousand years, it would do absolutely nothing! Now why is that? You know, what happens is that DNA gets activated. We call these transcription factors that arise from the cellular networks, and which determine how the DNA is expressed. And that's of course why our heart cells are different from our bone cells, which are different from our liver cells, and they've all got the same genome. It gets worse! I mean, the same genome in a caterpillar and a butterfly produces two totally different creatures! What's happening there? Again, during the metamorphosis, the signals to the genome to say which gene should be expressed and which should not, change. And so, I would say that the DNA is like a template. Actually, I wasn't the first person to say that. Jim Watson said that! Or was it Crick who said it to Watson? I can't remember which way it was, but one of them said to the other, "You know what? This is a template." They got it right the first time! And then they convinced [?] the central dogma of molecular biology. Well, you know, let's forgive them for that. The fact is that it acts like a template in the sense that, just as with a template when you want to make a guitar, for example, you want that shape to make the wood be the right shape. So you have a template for that. In a similar way, the genome sequences are used by the machinery that does the reading of the genome to ensure that you get an RNA of the right sequence, which then goes trundling off to a ribosome, which enables that sequence then to be converted into protein. But what activates all of that? What is the active process is exactly what Barbara McClintock said. It's the rest of the cell that tells the genome what to do.

14:36

AW: So, you just used the word "machinery" in reference to these cellular parts interacting with DNA, and I wanna just follow that thread for a moment. I think the word "machinery" implies a sort of determinism about what this cellular machine is doing, and you've made a big deal out of the idea that there's stochasticity in cells, and that can relieve cells from this deterministic fate. So can we just talk about that for a moment, and let's get into it carefully maybe, and define first of all what is determinism? And then what is stochasticity, and how does stochasticity lead us out of this deterministic trap?

DN: Yes, the deterministic trap was set way back in about 1665 by the French philosopher René Descartes. He wrote, in his Treatise on the Foetus—he was quite a scientist actually. In those days of course you didn't distinguish between philosophers and scientists. [interference] They're all thinkers. Now, what he did is he wrote, you know almost like the central dogma of molecular biology, he said, "If I knew what was in that sperm"—semen was the word he used actually—"I would be able to predict with certainty"—he actually emphasised it—"mathematically what would happen, the organism and its actions". That's all the way back 300 odd years ago. Now, you can trace that sequence all the way through to various 19th-century mathematicians like Laplace, and right the way through to a very important person in this particular discussion, which is Erwin Schrödinger. Now, your listeners may know that he was one of the great physicists in relation to quantum mechanics. He was also very good at relativity, and he wrote a book in 1942 called What is Life? There's a nice big question for you. Now, he correctly predicted—remember in 1942, no one knew the genetic material was DNA—he correctly predicted that when it was found, the DNA would be found to be what he called an aperiodic crystal. And if you think of a linear molecule that's been a little like a crystal, aperiodic because it doesn't completely repeat. There are some repeats of course, but if it was all repeat it wouldn't mean very much. And I think he was then thinking very much like a crystallographer. In those days, crystallography was developing very well in biology. And he imagined that like a crystal being observed with x-rays, with diffraction, you could determinately read that aperiodic crystal, which we now know is DNA. Now he then went on in that book to realise the made a mistake. And his mistake was—you know, in physics at the molecular level you've got stochasticity all over the place. You know, the molecules, the gas molecules in a balloon for example are bouncing this way, that way, and every which way. Now, what happens at the level of the balloon? The pressure, and the volume, and the temperature are determinate. Moreover, if you change the amount of gas, and you do various things to it, it's all determinate equations at the level of the whole balloon. You can see where I'm getting at now: The cell is a bit like a balloon. Now, what I'm saying is that he also knew that down at the level of the molecules there had to be stochasticity, and he wrote himself saying, you know, "what I've just said is absurd!" Now, I won't bother your audience with the little trick by which he jumped out of this dilemma, but he was responsible for Watson and Crick then saying, well formulating, what they call the central dogma of molecular biology, which of course is partly the idea that there's coding going only one way—that's correct—that DNA sequences code for RNA sequences, which then code for amino acid sequences; it doesn't go the other way. That's absolutely correct. But with regard to determinate readout, what do we actually find when we look at cells in culture? So, we've got a large number of cells. We find the expression level of any given protein is hugely variable! It can be varying as much as a thousand-fold between one cell and the next. There is massive stochasticity there. Moreover, the copying of the DNA is itself an error-creating process. Every 10,000 or so base pairs—remember, there are 3 billion in the whole genome—every 10,000 or so, normally you get a copying error. So the DNA itself doesn't actually reproduce very accurately. If you had those millions of errors in a genome, you wouldn't survive. Now what I come to is this: what happens to the rest of the cell? You can guess what I'm going to say. It comes in and it corrects those errors, so much so that usually the copying of DNA from one cell to a daughter cell, and down through generations, creates only about one error or even less in a whole genome. So the correction mechanism is superb. Schrödinger didn't know that. So you've got massive stochasticity, both in the way in which DNA functions—there are errors that accumulate in the DNA at quite a high rate—you've got correction of those, and you've also got great stochasticity in the way in which individual genes are expressed in particular cells, in a population of cells. So stochasticity is there, and it's very large.

21:20

MM: So Denis, I'm sorry Art if I can interrupt quickly, I'm selfishly interested in immunology. Could you speak a little bit about the role of stochasticity in immunology, and especially maybe taking it into another dimension that we wanted to make sure that we'd touch on in this section. You say, in a talk you gave I guess in Oxford in 2016 December, that it's functionality that's inherited.

DN: Yes.

MM: So if you can put the pieces together of this sort of functional inheritance of stochasticity when it comes to the immune system.

DN: I'll try. Yes, of course the immune system is a good example of evolution within a population of cells within an individual organism, you or me. But you can apply the same principles to inheritance going down generations. But let's focus now on the immune system; what does it do? It uses stochasticity in the most marvellous way. You see, the DNA sequence that codes for the protein that enables an attack to be made on the invading whatever-it-is—virus or bacterium or any other particle for that matter—what that protein does, it's an immunoglobulin just to give its technical name, is this: The immune system keeps the part of the protein that makes it an immunoglobulin; makes it possible to carry out its function of grabbing or latching onto a foreign body. It keeps that constant. And the part of the molecule that could be the kind of key to fit into the lock of the invader, and latch onto it and hold it, that bit hyper-mutates. "Hyper" means going very rapidly. Now it doesn't do so just ten-fold, hundred-fold, a thousand-fold, it does it one-hundred thousand to a million-fold. So what it's doing is spinning and using stochasticity there. Now what that does is, the different cells that spin will produce many many many different cells with different immunoglobulins. The system then uses natural selection of those cells—so natural selection comes into it, not denying that—to then allow those cells to reproduce, that produced the immunoglobulins that attacks and latches onto and holds the foreign body. The rest are allowed to die. So, now why is that purposive? It's purposive by definition. You see, what you've got there is an environmental challenge, which is the foreign body. You then have signalling from the surface membranes of the cells that detect the foreign body to trigger the hyper-mutation, because it doesn't happen unless there's a trigger. So that part of the system is nicely targeted because it means, as you receive the signal that there's a foreign body, hyper-mutation occurs. You then have signalling from the rest of the system to effectively say to those cells that fail—and most will, to get a good match, a good key to go into that lock of the invading body—die. And you then reproduce from the cells that produce the right attachment. What then happens of course is, as we well know, the foreign body is latched onto, it can be taken in to the cells that clean the body up—the phagocytes and so on, cells as it were expert at cleaning the body up—and they gobble it up. You've got to lock onto it first. So it uses stochasticity in a beautiful feedback mechanism. If that was in a rocket you'd call it a guided rocket, wouldn't you?

(AW laughs)

24:51

DN: Right? It's not a rocket that's just simply fired, and goes anywhere, and you can't as it were move it this way or that way. It's clearly guided, but that's what we mean by a functional process! And what I know many of my colleagues who disagree with me would say is, "well, but Denis it's still mechanism isn't it?" See, yes but it's guided mechanism. Where does the guidance come from? It comes from within the system itself. In a sort of sense it knows what it's doing, I know that is a metaphor.

(DN, AW and MM laugh)

DN: Yes, but it's hard to avoid the view that that is guided. And you know, if you watch the cells, which we call phagocytes and so on, wondering around looking for stuff to pick up, to clean up, it's very hard not to think that those cells—they're not like billiard balls just being bounced around in a mechanical way. They're feeling this way, sniffing what's come up, going away from it if isn't worth investigating, sending a [word?] to another area, and when they find something that's right, very quickly (makes gobbling sound) they gobble it up. You know it's a process which if you watch that you'll have to say that's a guided process. Now guidance is not from something right out there, some mysterious, spiritual process. It's a very simple, physiological, or engineering if you like—because engineers can make such guided processes—it's a perfectly simple way in which you end up with functionality, guided functionality, and I would say it's perfectly proper then to use the word that this is a process which goes in a particular direction. Now that leads me to the point that evolution can use that, and it does Organisms do choose to go, and I use the word "choice" quite carefully here, because if you watch those phagocytes going around and looking to clean up the body, they're certainly choosing to go that way or that way depending on what they find. I mean what do we do when we look around and see what we want to have to eat? [word] Look at what that looks like, the oranges over there are not very good, the apples over here look brilliant, so we buy apples [word?]

AW: That's a good description of how I stumble around the supermarket. I'm sort of stochastic, and yet I still couldn't find a pretty good meal if I stumble for long enough.

27:22

(MM and DN laugh)

DN: [word] that kind of guidance as a word to us, I think you have to give it those phagocytes.

AW: Yeah. Denis, I wanted to ask a related question about molecular stochasticity and take on a really big question, and I think I know approximately what your point of view will be about this, but do you think humans have free will? And if so, does it arise from this process of molecular stochasticity?

DN: That's a huge question!

(MM laughs)

DN: And I will do my best with it. It's an area I'm actually seriously working on with philosophers at the moment, because I think this is a conceptual question as much as an empirical one. What I mean by that is first of all, I'm not totally sure that I'm happy with the word free will. Let me just say briefly why, and then I'll come to the [word?] of your question. You see, complete freedom would be useless, wouldn't it? I mean when we're acting freely, we're not really talking about going every which way. Well I suppose occasionally we do. What you described you doing in the supermarket might come close to that, but nevertheless most of the time we have some idea of what we want to do and where we go, and so on. Already there are constraints within the logic of our own behaviour within the interaction with other organisms and other humans. There's already a lot of constraint within which, if we are free to act in different ways than what we actually chose to do, then there's a lot of constraint over that freedom. So I sometimes worry about the simple expression "free will". It's not entirely free all over the place.

AW: Agreed.

DN: Now we come to the question you really asked: Could stochasticity be part of the answer? It's a very deep, philosophical question, that. And there are philosophers who think you can marry the concept of free action even with determinism. There are very good examples of that in Western Philosophy. They may or may not be right, I don't know; I don't know how to judge that. But what I do think is this: If you've got stochasticity, you've got a vastly better opportunity for—how best to put this now? Trying out different ways, just as the immune system is as it were selecting from that vast canopy of different cells that are produced by the hyper-mutation process, and selecting out just the ones that work. We can do the same! We can play around. I don't know what goes around in my mind when I sleep, and find I've got the solution to a problem the next morning. But I think part of what may be going on is that I'm worrying about it—I go to sleep worrying about it—and, you know, low and behold, don't solve it the previous night. But the next morning, I wake up and think "goodness, I think I can see the way through that." What was going on there? I don't know exactly. Does anybody know what's happening when you're sleeping? But seriously what I think might be happening is that your system somewhere up here goes on spinning around. And I think you might be able to develop a theory of free action—what we mean by free action, which I clarified earlier on—I think you might be able to develop a theory of free action after that. But let's be careful, I don't think this can be done just by scientists alone. I think this is a place where we need the conceptual tools and skills of good philosophers, and you need good scientists too to interact with them.

31:19

AW: That's good that you just said that, because I was just thinking at a more mechanistic level, you know, what we need is for the neurobiologists to tell us how much of our thought process and our memories come out of molecular stochastic effects on the neurons in our brains while we're sleeping, but maybe that's not the way forward in resolving this question.

DN: I just don't know. I think that that those are bigger questions. Where would stochasticity come from, and there could be many levels at which it might occur. I don't know yet.

MM: Before we move onto a totally different topic, I'm intrigued to be maybe challenge you, Denis, on the additional implications of evolution as a directed process. I mean in a general sense or, you know, it's been fun to talk about free will and the implications for people in particular so if evolution is directed, why should the general public care? How does that change our impression of day-to-day lives of people, socially, economically, whatever that might be?

DN: You know where the greatest use of Selfish Gene Theory has occurred? It's in economics. The equations for which quite a number of Nobel Prizes have been awarded, particular from the Chicagoan School of Economics, are very similar to the equations of evolutionary biology. They're expressing, more or less, just to be technical for a moment—this is equations like Price Equations, various equilibria. I mean the Nash Equilibrium in economics is that kind of approach—we don't want to get too technical here, but I think it's correct to say that the implications of the use of the equations of evolutionary biology—game theory essentially—in economics have led to very many developments, which need to be reexamined. If you think, as I do, that evolution is not a fully guided process of course, but at least partially guided. Because that leads you to a number of ways in which you can see that the interactions between organisms are much more complex than the simple selfish versus cooperative view would suggest. Let me give you one example: Those monkeys and dogs can detect cheaters amongst their number. I don't mean cheetah the fast-running animal, I mean cheaters.

MM: They're not playing by the rules.

DN: They don't play by the rules, don't share food properly, and so on. They tend to exclude them. Now, there are many ways in which you can think about that, but one way to think about it is that cooperativity is actually more rampant in the interactions between organisms than you might think. This was one of the points that Lynn Margulis used to make a lot when she was alive in a marvellous debate that I chaired back in 2009 between Lynn Margulis and Richard Dawkins. Lynn was the person who championed the idea, she never said she invented the idea or was the first to demonstrate it, but she championed the idea that many of the components of the cells in our bodies—eukaryotic cells to use the technical term, things like mitochondria, ribosomes, and so on—came from the fusion of organisms to produce a form of cooperation that made a real big jump in the evolutionary process. And whatever you say, the emergence of eukaryotes—that's cells in bodies like yours or mine and in plants and in most animals, multicellular organisms—those cells have got an extraordinary degree of complexity. Her view was that has come about through symbiosis; that is, cooperation between organisms. One organism effectively either ingesting the other or you could say the other has invaded the first one, but then we come to a matter of language; what you describe it as. What happened of course, and what happened in relation to the formation of mitochondria—those are the little bits inside our cells that give us energy vastly more efficiently than it would be the case if we didn't have those there—but those were originally bacteria. Can you believe it! Every cell in your or my body has in origin large numbers of bacteria. It's not just in our gut, which of course you've got many bacteria in that help us to digest our food, but even within the cells themselves you've got the remnants of bacteria that one time fused with other cells to produce the kinds of cells that we've got in our body.

36:31

DN: What Lynn Margulis would say, if she were here taking part of this debate, is that cooperation is rampant in the way in which evolution has occurred.

MM: Fair enough. So, I do wanna maybe change levels a little bit. And maybe dive back into the more mechanistic side of things, and really push you on systems biology. It's not exactly an easy topic to talk about, and we've already hit on some pretty complicated things but this one might be among the most daunting. So what do you think about the future of systems biology. I mean, how do you see it coming into play to influence the practice and the inference we're going to get from biological research in the next several years?

DN: Well, molecular biology has been extraordinarily successful at characterising the components, the molecular components of cells, tissues and organs, and so on. And it's also been spectacularly successful in decoding or rather sequencing, and I think we're getting to know the code, of the genetic material called DNA. All of that I would give molecular biology a cheer from the sidelines. No problem with that at all. Very, very important discoveries. The difficulty comes back though to what I said earlier on: the molecule DNA. And if I put that in a petri dish with as much fluid and nutrients as you like, it would do absolutely nothing. Now, what makes it do it would be what we said earlier on was that the system—now what I mean by the system, I mean the whole cell with its networks of membranes, and many proteins interacting in those membranes and with each other, and with many components that are not themselves coded for by DNA—that network operates like, well, I would say a little bit like a computer itself. Now it may not be a determinate computer; remember stochasticity, it may be a stochastic computer. But what it's doing is effectively telling, this is Barbara McClintock's direction of causality of course, it's telling the genome what to do. Now I regard that study of what tells what what to do to be the function of systems biology; the purpose of systems biology: to work out those interactions and be able to find out how it can be that a liver cell gives rise to a liver cell as it divides, and a heart cell to a heart cell, and so on. In other words, how it can be that those messages from the system as a whole go to the genome to tell it what to do. So part of my characterisation of systems biology would be that it is those networks of interaction. But now I come to the point I made just slightly earlier on. Multi-level, because you see we not only go from molecules to the networks of molecules within all of those membraneous structures in cells, we also go to the fact that cells join to form great long strings and sheets and various shapes and structures, like our muscles and our tendons and our hearts and so on. The tissues of the body through to the whole organ, through of course to the whole systems of the organism, and then to the organism as a whole. Now I come to the real point. When I analysed, many years ago, the way in which heart rhythm occurs, I had to operate at at least two levels in order to work that out. One was the whole cell, with its electrical potential and all the various parameters that depend upon the whole cell. The other was the individual proteins forming and carrying the electric current, which enables the heart-beating origin, its pacemaking activities and electrical phenomenon. I worked out how that could interact with the cell as a whole to produce the rhythm, such that if you took all of those proteins out, and you put those in a petri dish—I like the petri dish experiment.

40:50

(AW and MM laugh)

DN: Put those into a petri dish without the complete cell, there's no cardiac rhythm! You can have all of those molecules there. No rhythm unless you have a complete cell. So there can be feedback from the cells' full electric potential onto those proteins. So one of the, well I'm praising myself here now. One of the most spectacular, early uses of the systems approach in biology—which was the working-out of how the cardiac pacemaker operates, which is my field—had to use multi-level interaction in order to understand what was going on. So I think the way forward is to try to work at a multi-level approach so that we take account of the fact that it's not any cells that tell their proteins what to do, but also tissues that interact so that the cells in this part of the tissue are talking to the cells in that part of the tissue. And in the heart for example, the cells in one part are talking is a complete [word?] fact, a complete connected network of cells that spread the wave excitation all the way through them.

MM: Yeah, I think that everything you articulated about systems biology, it's fascinating, and at the same time I guess I'm hung up on the terrifying—I think is the right word—complexity of how to do the research when just at one level, I mean the potential interactions among molecules in a cell (takes deep breath) oh my goodness. And then you say, "well okay, deal with that, and don't forget that there's populations and communities and an entire ecosphere that you might wanna consider." I mean Denis, what do we do?

DN: What we do is we become physiologists.

(All laugh)

DN: I'll tell you what physiologists are very good at.

MM: We're in agreement there. You definitely got Art on that same page with you.

DN: Well you see, what physiologists are very good at is making sense out of the incomplete data. Now that's saying something, it's quite a claim, but you know it's not far from the truth! Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley who worked out the nerve impulse—that was about 1952. They produced their equations, famous equations for the nerve impulse. It got them the Nobel Prize in 1963—what were they doing during the war? They were employed in radar. And precisely on the ground, what you get in early radar particularly, you know you get those rather faint images; something over there. And it was the skill of the physiologist in drawing conclusions from incomplete data, from data that wasn't absolutely definite. Now, why do we have that skill? We have to, because we couldn't do physiology without it! We couldn't be operating at the level which we often operate at, say the whole muscle or the whole tissue or the whole organ, if we did not have that skill. Otherwise it's vastly too complicated.

44:03

MM: Is it possible to come up with a title of that grand, grand proposal as it were? To serve as a rallying cry for the group? And what I'm thinking about is something that's been proposed, you might have seen it, a recent book by Geoffrey West called Scale, is one of the originators of metabolic theory of ecology. I mean, is it possible to unite everyone under a sort of effort of going for those grand equations in biology?

DN: Yes, I have a lot of respect for mathematics in biology, otherwise I wouldn't have been doing what I've been doing for 50 years. I like to encourage all of that too, I think that the various approaches that could give us a little bit better grasp of the systems—here I'm talking about systems in a slightly different sense, isn't it? There are many senses of system of course, that's part of the difficulty—we're now talking about how you can characterise using clever mathematical approaches, some very very complicated processes, and end up with an analysis which is a bit simpler than being shocked by the total number of combinations of interactions that there could be. But I'm also a bit doubtful about whether there's going to be a complete mathematisation of biology in the way that you could say there's a complete mathematisation of physics, and if some of the claims of theoretical chemists are correct, a complete mathematisation of chemistry. I think the difficulty is that too much of biology is serendipitous. Back to stochasticity again. And so, okay, I'll have to do some very clever mathematics to incorporate that stochasticity, and I wish good luck to people [interference] who try to do that. I do recognise also though, that although I had a period when I wasn't too bad at mathematics, after all that's what got me being chosen by the faculty at Oxford to examine a particular thesis. The fact is, I don't think I'm any longer good enough to do that kind of mathematics. So I cheer from the sidelines as those that have got better mathematical skills have a go at seeing what they can do. Whether they'll succeed, I don't know. We'll have to see. But you raised a very important question: is there something, a kind of banner that we can gather around? I've just been at a big congress of the physiological sciences. It's four-yearly, annual—not annual, four-yearly cycle of world congresses of physiological sciences. And one of our missions, which we produced a big report on at that congress was the mission to return physiology to centre stage. That's the quote as it were.

47:13

DN: Now, I think that it's conceivable that the world of physiology can find a way back onto centre stage, partly because of what we said earlier on about re-thinking evolutionary biology. You see if you really believe that it's all stochasticity followed by natural selection, physiology has no role other than to explain why natural selection succeeds in selecting A rather than B; there's a physiological reason for that. It's got no role at all in the process that leads to that variation in the first place. But if what I'm saying is correct, and I'm not alone now in saying this by any means, then physiology does have a role. Going back to that guided process of stochastic variation, seeking as it were for a solution to a challenge from the environment—so you've got a complete feedback loop there—that is a physiological process. And that is what I think partially guides evolution. Now if we're back in business as contributing, as I think we should, take maternal effects for example that pass down generations. The fact that if you have babies that are born too small to mothers that were starved has happened for example in the Starvation Winter in Holland in 1942. You can follow that down through the generations and find that the children and the grandchildren are affected, and now we're getting to the third generation of course to see that these are physiological processes, they're grand problems that we have to face in relation to our understanding the influence of environment on health and disease, and how much of that is transmitted. And I think therefore that physiology is very much, in this newer view of evolutionary biology, I think it's very much in contention.

MM: Well Denis, I can't let you go, and we've touched on it a little bit. So if you feel that you've said your piece, we'll understand, but do you think we're in or entering a golden age of biology? Are we going to look back in 50 years and decide this was a special time?

DN: I think we are, I think we're at a very exciting time. I think it is one of the best times to be in biology. And my message to the young people is that there are fantastic opportunities now. I think you see, that for about 70 years we were in a bit of a straitjacket. Yes, the modern synthesis—that was the synthesis of evolutionary biology back in 1942 that Julian Huxley's book of that title, The Modern Synthesis. It was brilliant, and it spawned population genetics, it produced a quantification of that kind of field of biology. But you know, theories that are 70 years old deserve a bit of revisiting, don't they?

(MM laughs)

50:17

DN: You know, what theory in physiology would we have not have revisited in that period? Now, I'm joking a little bit. I can tell you the answer that my colleagues who are much more classical, Neo-Darwinists would say. "Oh, Denis, we've absorbed all kinds of new things. Genetic drift, and various forms of ways in which genomes can get reorganised. So we'll take Barbara McClintock's work and say, you know, that's alright. Those are big mutations, they're not small mutations." I will say to them, well, but that's what your original theory was. See what I think has happened is that progressively they have actually expanded the theory. But they're not too good at admitting that that has changed the theory, and the original one as formulated by August Weissman all those years ago at the end of the 19th century is incorrect! I think we should say it's incorrect. And I don't mind whether people want to call whatever they develop out of this, one thing or another. I don't think we need to get stuck on names, but I think there are some exciting new trends. Incidentally, that was the title of a big meeting held here in the UK last November, which it just about published in an issue of the Journal of the Royal Society. So even major national academies have taken these issues very seriously. So, exciting time to young people out there wondering whether to get into it. I think this is just the time.

MM: Well Denis, wow. Thank you so much. It's been a lot of fun, we really appreciate your time and your patience to finally have worked out a time that works for all of us. We'll let you go and maybe get some rest.

DN: Okay, thank you both!

AW: Thanks very much, Denis!

AW: Special thanks to Matt Blois for editing and production help. Thanks also to Gerard Sapes, Roman Wasso, Devan O'Brian, Steven Lane, Victoria Dahlhoff, Haley Hansen, Holly Kilvitis, Travis Flock, Meredith Kernbach, Chloe Ramsay, Jeff Oberdane, [name?], Cynthia Downs, and Susan Miller. [spelling?]